Battle in the house? – The European Parliament initiates proceedings against the European Commission

Tension between Hungary and Poland and the European Parliament has considerable increased in the past years. The Parliament has been speaking up against these countries openly and was pressuring the Commission to take measures against these Member States. Roberta Metsola’s

Family matters – Irish voters against constitutional change

Ireland is known for its conservative constitution and direct democratic system, relying on referendum in most major government decisions. Article 46 of their Constitution prescribes submission of a Referendum for every amendment proposal of the Constitution to the decision of

Rule of Law and Academic Freedom (?): Reflections on Hungary’s Case with the Planned Suspension of Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe Funds

In January 2023, the European Commission announced the potential suspension of Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe funds for 21 Hungarian universities. While the discussion is still ongoing, some early conclusions could be drawn on whether this measure complies with the rule

Hungary -now- in the SPOtlight of the Venice Commission

Recently, my colleague - also my professor and editor of Constitutional Discourse - Márton Sulyok published his article and gave us his opinion on the newly created Sovereignty Protection Office of Hungary and the law that established it, namely the

Protecting Constitutional Identity through Sovereignty? Framing the Mission of the Hungarian Sovereignty Protection Office

Three weeks ago the Hungarian Sovereignty Protection Office began its operation. Some theoretical and practical implications are analyzed below given the EU’s newest infringement proceedings launched early February as a sign of “tough love” – an early Valentine’s Day present.

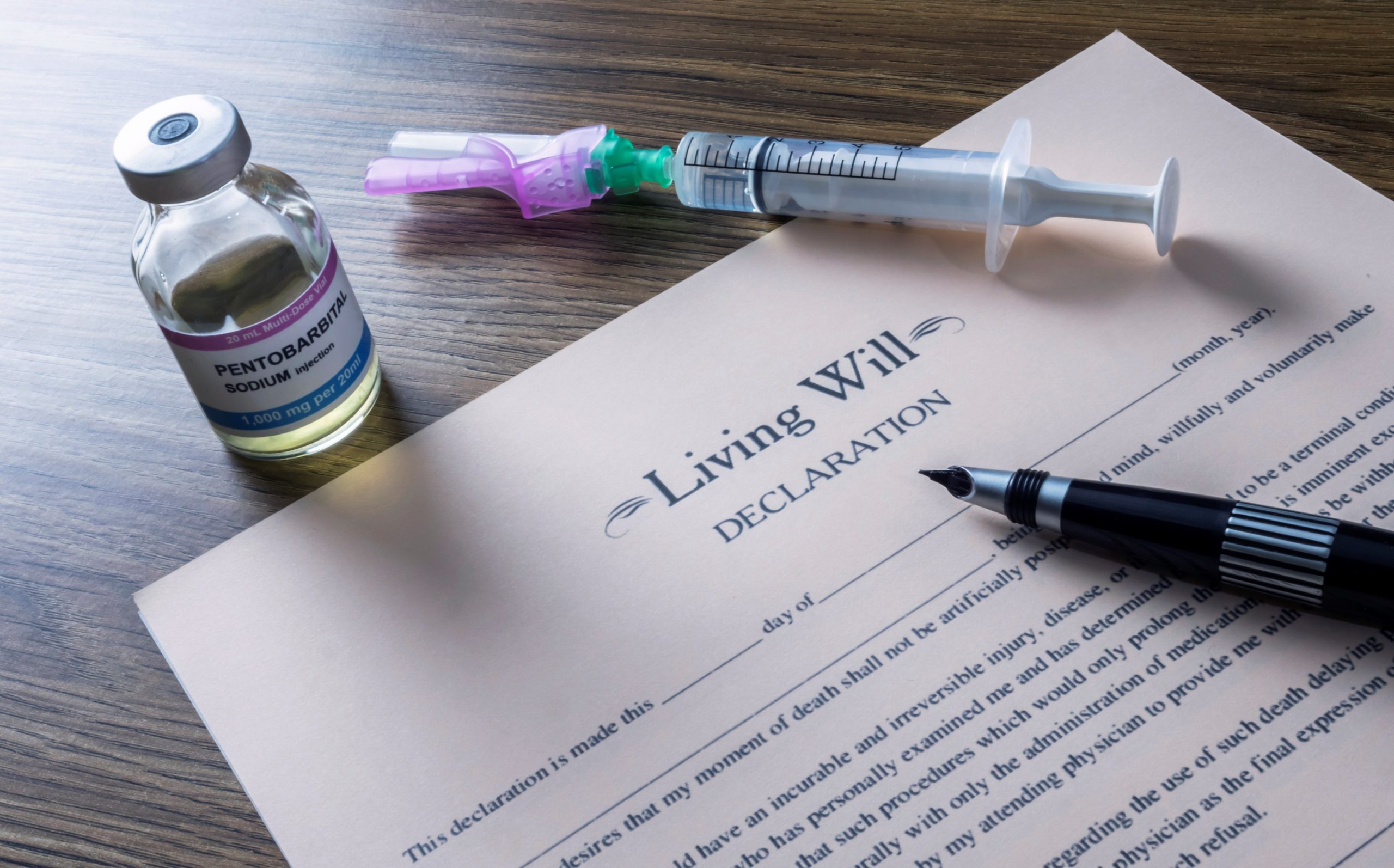

On The Value of Guilt and Moral Charges – Anticipating the ECtHR’s Judgment in Karsai v. Hungary

In the wake of the summer of 2015, a solemn prognosis was delivered by a leading physician at the Medical Centre of the Hungarian Defense Forces. The news foretold a gradual decline in my liver function, painting a stark reality

Márton SULYOK: Pitch Black in Strasbourg or a Bright, Sunshiny Day? Constitutional Identity and Anti-Discrimination in Context

2023 marks the thirtieth anniversary of the accession of my home country (Hungary) to the ECHR. A perfect time for stocktaking in the jurisprudence of the ECtHR regarding issues that might define the next 30 years. This is where constitutional

Soma BÁCSFALVI: Constitutional Contradictions of Constitutionalism in the Global North

As in my previous blog post I tried to make a brief comment about some of the different views (or progress) of the rule of law principle/value, in that article, I did not write about the French system since it

Gergely DOBOZI: Mind the Preamble, Friends!

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Particularly during the peak of summer, this well-known cliché looks like a good opportunity to set the stage for an opinion piece concerning some aspects of the future of

Gergely DOBOZI: Barbed Hooks and the Rule of Law

Probably everyone has seen a hook in their life regardless if it is barbless or barbed. On the latter, the barb serves to secure the hook in place once it has pierced the fish's mouth. Well, the Rule of Law