Is It Allowed to Lie?

Boundaries to freedom of expression during the election campaign period

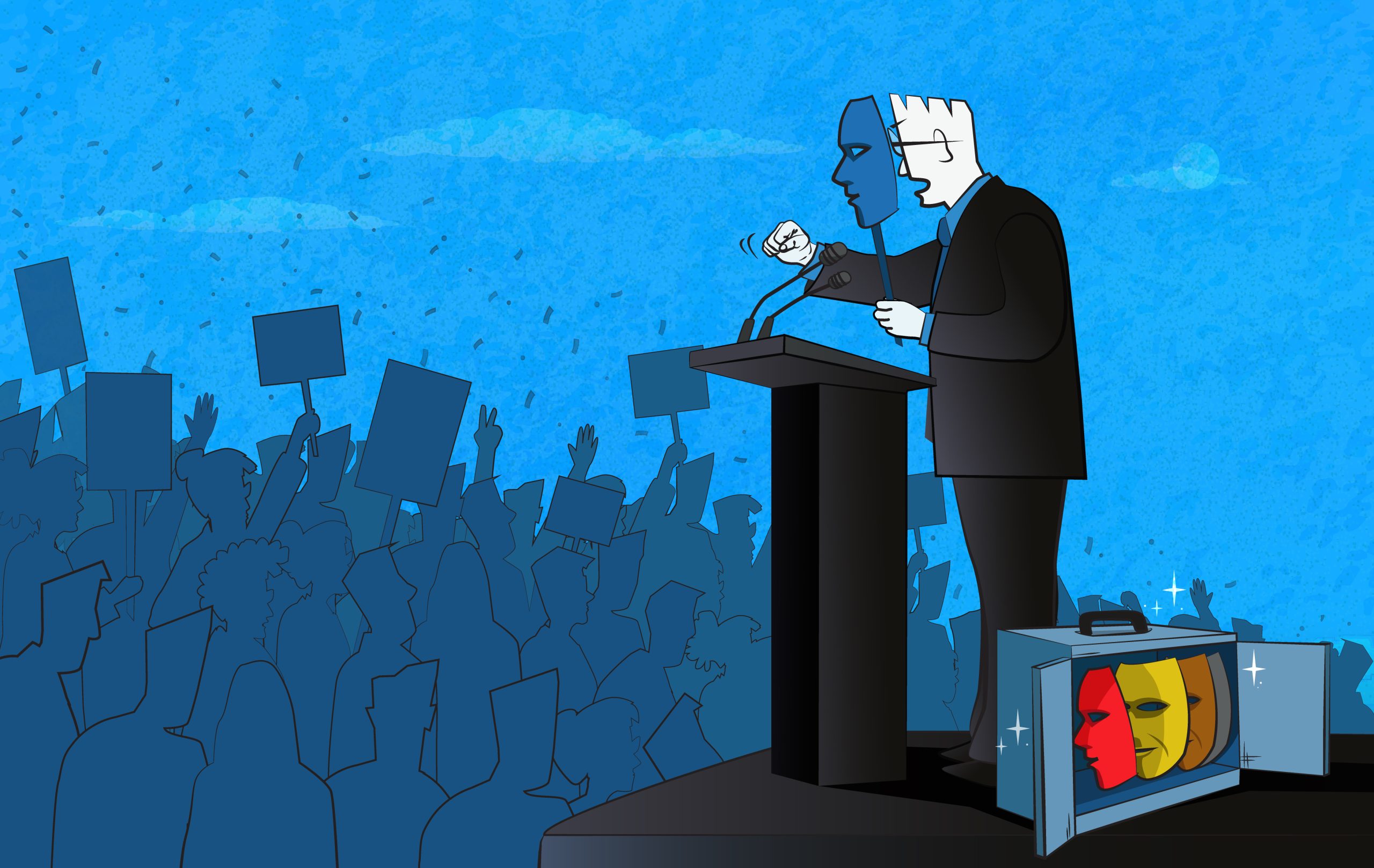

The year 2024 is an election year for the whole European Union in view of the European Parliament elections. This is particularly true in Hungary, where local elections are held on the same day as the European Parliament elections. This gives special relevance to the long-standing and rather provocative question of whether it is allowed to lie in an election campaign. The election campaign is one of the most important platforms for political discourse.[1] The main function of the campaign period is to enable citizens to make informed choices. And in this approach, electoral campaigning is an activity aimed at influencing voters, which can take many forms, with objectives ranging from simply encouraging participation, to negative (who not to vote for) and positive (dissemination of information) campaigning.[2] However, this purpose of the election campaign often comes into collision with the constitutional boundaries of freedom of expression. In order to influence and persuade voters, the messages and allegations made by each candidate are often exaggerated and sometimes even contain untrue information about the other candidate. In these cases, the question arises as to where the boundaries of free expression lie. More radically, is it also free to lie during the election campaign period?

This issue has been raised several times in the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court (see, inter alia, Decision no. 3107/2018 (IV. 9.) AB, where the Court had to decide whether the following statement—despite its falsity—enjoys the protection of freedom of expression: “your MP, Bence Tuzson, has only once since 2014 pronounced the name of Fót in Parliament”). In these decisions, the Hungarian Constitutional Court also uses the concept of “political expression” in addition to the concepts of value judgment and factual statement. This concept partially blurs the boundaries between the categories of value judgments and factual statements. The Hungarian Constitutional Court has developed a test to determine whether or not a statement made during a campaign period is admissible.

- The first element to be examined is whether the statement made can be regarded as speech on public affairs. Indeed, freedom of expression in the context of public affairs is particularly strongly protected by the fundamental law, since it is an essential part of the expression of opinions concerning the activities, views, or credibility of those who shape public affairs. A significant part of social and political debates consists of public actors and participants in public debates criticizing each other’s ideas, political performance, and, in this context, each other’s personalities. So, in principle, we can only apply special rules to the assessment of a statement if it can be considered to be speech relating to public affairs.

- This specific test is therefore only applicable when the speech takes place in political debates, in particular in election campaigns. It is important to note, however, that in the practice of the Hungarian Constitutional Court, there are several decisions (see e.g. Decision no. 3217/2020 (VI. 19), where this more permissive test was applied despite the fact that the disputed speech did not take place during an election campaign.

- An important feature of the test used in political debates is that the assessment of a controversial statement should not be made solely on the basis of its direct content, but should be made in the light of the heightened circumstances of the election campaign and all the circumstances of the case, and with a view to allowing the candidates to criticize each other’s programs and suitability as freely as possible. And this brings us to the most important reason for creating the test, which is also the most important purpose of election campaigns. The free flow of information and opinions is the only way to ensure that voters have the widest possible knowledge of the criteria on the basis of which they will make their decisions on election day. This is why the extent to which the media marketplace and advertising space is considered free and accessible to individual candidates is of paramount importance in the establishment of an electoral system. One of the criteria for the constitutionality of an electoral system[3] is therefore that the electoral system of the country in question guarantees freedom of expression during the electoral campaign and the electoral process, and ensures the right of voters to be informed. The purpose of an election campaign is clearly to influence the will of the electorate and to convince them which party they should vote for. This is only possible if we ensure the free flow of opinions and the full exercise of the right to information. In this respect, it is worth highlighting a decision of the Slovenian and Serbian Constitutional Courts. In a 2011 decision, the Slovenian Constitutional Court ruled that elections can only be fair if the election campaign is widely informed, i.e. elections or referendums can only be considered fair if they express the real will of the people and if the public has been widely and comprehensively informed during the campaign.[4] In 2015, the Constitutional Court of Serbia ruled in its decision no. Uz-6600/2015/SR-0167 that freedom of expression must be guaranteed in election campaigns.

- In connection with political disputes, it is therefore important to emphasize that, according to the Hungarian Constitutional Court, the determination of the factual statements formulated in this context cannot be made by the automatic application of the test of provability in the ordinary sense, i.e. it cannot be limited to the assessment of the literal content of the statement under investigation. It is not enough to show that certain elements of the speech under investigation can be objectively and factually refuted in order to hold the participants in an intense debate on public affairs legally liable. The contested statement should also be assessed in the light of its true meaning for the electorate. This assessment is determined by the fact that, in the democratic debate on public affairs, citizens who interpret the debate in their own context are aware of the characteristics of party political expressions that are prone to attention-seeking and exaggeration. The balancing exercise therefore clearly goes beyond the examination of the statement by the test of provability and requires an assessment of all the circumstances of the case. If the superimposed statements relate directly to the political activity, program, credibility, or suitability of the candidates, even if they are made in a declaratory form, there is a presumption that the communication is an opinion. The exaggerated or astonishing formulation of criticism may also be protected, even if the exaggeration may concern a factual issue. Moreover, in case of doubt, the assessment may also rely on the fact that there is ample opportunity for factual rebuttal of certain details.

Thus, the Hungarian Constitutional Court has addressed the issue in several decisions, and found that certain statements of fact in an election campaign must be assessed as political opinions (and thus are subject to a higher duty of tolerance) if they can be properly interpreted by voters in the context of the election campaign and their underlying political message can be clearly identified. This approach helps to provide information to a wider audience.

The Hungarian Constitutional Court has therefore taken a relatively permissive position on the issue. This permissive position is based primarily on the assumption of the correctness of the voters’ judgment. In other words, the ability of voters to interpret and manage the electoral campaign around them at their local level. The correctness or incorrectness of this assumption is itself open to debate. Importantly, the constitutional arrangements of the 21st century (as opposed to the 19th century and the early 20th century) do not require voters to be “aware” enough to make a politically considered decision, taking into account economic and other social considerations, when casting their vote. On the contrary, trends (see, for example, the UN CRPD Commission’s report on Tunisia[5]) point in the direction of ensuring that no one is excluded from the right to vote for any reason. On this basis, it becomes questionable whether a voter can actually interpret a statement made in a campaign as not being a statement of fact, but merely a “political opinion”. At the same time, of course, it would not be right to see voters as helpless individuals who cannot make sense of a dialogue between political actors, often full of emotion and passion. Dialogue, because we must not forget that between political actors, giving rebuttals is part of communication, even an essential feature. If the two parties in the debate are indeed rivals, then the refutation of the claims made will be an integral part of the debate. And in this case, the voters no longer have to interpret just one statement, which may be ambiguous, but two contradictory statements in the debate. This, in my view, confirms the premise that political debates should be given more space (while respecting the constitutional rules of the game) than the facts that are presented in non-political debates.

Finally, it is not possible to avoid the examination of the thesis, that was first stated in the Decision of the Hungarian Constitutional Court no. 3240/2019 (X. 17.) AB, which can also be interpreted as a kind of “moral clause”. This is because, although during election campaigns candidates have a wide range of tools at their disposal to persuade voters, where the boundaries between (political) opinions can be pushed, it is necessary to note that this does not mean that candidates are free to spread any untrue information or allegations about each other or to mislead voters with distorting statements or half-truths. The exaggerated or shocking statements made by candidates in their campaigns generate a negative process, the adverse effects of which are recognized by all candidates and which affect society as a whole. Manifestations that disregard good morals and good taste also morally qualify those who use such means. Freedom of expression, which is protected by fundamental rights, does not mean that all opportunities that are not unlawful and do not entail adverse legal consequences must be used. This is dictated not only by ethical considerations but also by the well-understood self-interest of all concerned. However, this “moral clause” has not yet been applied by the Hungarian Constitutional Court. And in line with the above, I think it is highly questionable in what case the Constitutional Court could say that speech in a political debate already violates this “moral clause”. And in view of the extension of boundaries, it might not be worth knowing.

Gábor Kurunczi JD, PhD is an Asst. Professor (Senior Lecturer) in the Department of Constitutional Law, Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Hungary. JD (2011, Pázmány), PhD in Law and Political Sciences (2019, Pázmány). Currently, Prof. Kurunczi is Chief Counselor to the Hungarian Constitutional Court.

[1] Péter Smuk: A demokratikus közvélemény formálódásának alkotmányos garanciái. Európai standardok és közép-európai szabályozások. In Medias Res 2014/1. 186. https://szakcikkadatbazis.hu/doc/4277436

[2] Ibid. 187. https://szakcikkadatbazis.hu/doc/4277436

[3] Gábor Kurunczi: Electoral Systems. In: Lóránt Csink – László Trócsányi: Comparative constitutionalism in Central Europe – Analysis on Certain Central and Eastern European Countries. CEA Publishing, Budapest, 2022. 423-440. https://real.mtak.hu/147534/1/CEALSCEPhD03ComparativeConstitutionalism22.pdf

[4] Decision of the Slovenian Constitutional Court no. U-I-67/09, Up-316/09 | SL-0168.

[5] Implementation of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Initial report submitted by Tunisia. CRPD/C/TUN/1. (https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g11/427/92/pdf/g1142792.pdf?token=QkoJC5RxBB1sq4WmFe&fe=true)